<

<

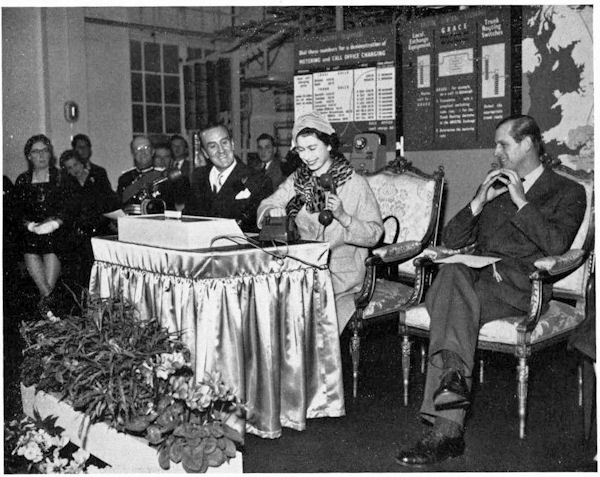

HM The Queen makes the first STD call. [POTJ - BT Archive]

Sam Hallas' Website

Continuing the series of articles I prepared for the Telecomms Heritage Journal about how certain folk cheated the phone system, some times it was fraud but at other times it was just for fun.

In the previous article we looked at the various ways that telephone users could cheat the telephone company and obtain free or cheap calls. Following the introduction of Subscriber Trunk Dialling (STD) to Britain in 1959 a new vista of mischief was opened up.

<

<

HM The Queen makes the first STD call. [POTJ - BT Archive]

![Click for larger image Magnetic drum translator [POTJ]](fiddling/translator_small.jpg)

Magnetic drum translator [POTJ]

The principle of dialling between local exchanges was explained in part one. A caller dialled digits forming a code which directly routed their call. STD changed the whole way in which calls were set up.

To set up a trunk call using STD a caller would dial a code consisting of the digit 0 followed by three digits which determined whereabouts in the country the call was going. The first two of these digits were written as letters, intended to be a mnemonic – AB for Aberdeen to YO for York, as examples. The third digit distinguished between destinations with the same two previous digits, usually in order of importance or expected traffic. It also separated destinations where the mnemonic letters used the same digit. So calls to Cardiff needed a code of 0CA2, to Cambridge 0CA3, Aberdeen 0AB4, Bath 0BA5 etcetera.

Only the initial 0 dialled by the caller had the effect of routing the call by connecting the caller to a “Register Translator”. The Register part of this equipment served to store the entire remainder of the called number. The Translator part converted the next three digits into the actual route that the call would take. It would send the routing digits into a new set of selectors forming a Trunk Exchange. The Register part would then send the rest of up to six digits to the trunk exchange to complete the call.

This is similar to the way calls were set up in the so-called Director areas – London, Birmingham, Liverpool, Manchester, Glasgow and Edinburgh. Here the first three digits were translated by the Director into a route which was sent to a set of selectors not accessible to the caller.

During the 1950s the Post Office had been busy setting up this automatic trunk switching network as part of its Trunk Mechanisation scheme which enabled it to introduce STD to the public.

I’m sure you’ve already worked out that if a caller could access this trunk network directly then the entire country would be at their fingertips to dial. Each major town designated as a Group Switching Centre would have trunk circuits to places with a significant amount of traffic, such as London and the nearest big city as well as at least one city which was a Zone Centre, interconnected with all the other Zones Centres. This would provide sufficient routing ability to reach all parts of the country.

It became clear by about 1970 that a back door entry to the trunk network had been wired into a number of telephone exchanges by the local technicians. This would enable them and their friends to make trunk calls either at local rate or even free.

A spare number unlikely to be dialled accidentally could used, such as a code starting 17. In order to make it hard to find, the circuit could be arranged to return unobtainable tone which would put off the casual dialler. Those in the know would either dial into the tone or wait until it went away. Both methods had been used in various places.

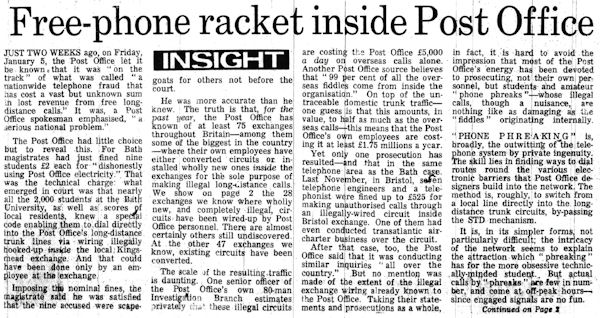

A story from Associated Press published in December 1972 spills the beans.

Post Office investigators found that Kingshead exchange in the historic city of Bath had been wired by a rogue technician. With a knowledge of the right codes to dial it became possible to call anywhere in Britain and even overseas. Of course this loophole became common knowledge among the University students and townspeople. The investigators feared that phantom wiremen had installed similar features elsewhere. A spokesman said, “This is a serious national problem. We are making investigations in other towns all over the country to get to the bottom of this fraud.”

The Sunday Times of 21st January 1973 reported:

“For the past year the Post Office has known that at least 75 exchanges throughout Britain – some of them the biggest in the country – where their own employees have either converted circuits or installed wholly new ones inside the exchanges for the sole purpose of making illegal long-distance calls.”

It’s hardly necessary to say that the curious folk with itchy dialling fingers would find these back doors into the trunk network.

One reported anomaly was that in certain places dialling into a town exchange from an adjacent town allowed the initial digit 1 to be dialled to access the trunk selectors. It was never clear whether this was a legitimate route or another back door.

Local telephone calls were carried over copper wires all the way. Dialling pulses could easily be sent by interrupting the line currents in the same way that a telephone signalled numbers to the exchange.

Once a telephone circuit became amplified to keep speech intelligible over longer distances, there was no longer a direct copper connections to carry dial pulses. A similar situation arose when telephone calls were combined in a carrier system sending dozens of calls down one cable, by radio or latterly by fibre optic.

An obvious means of overcoming this limitation was to use audio tones to signal line condition and status. The earliest system was known as System Signalling Alternating Current No 1 (SSAC 1) and it used two tones – 750Hz in the forward direction and 600 Hz in the backward direction.

A much improved system was introduced by about 1959, SSAC 9, which used a single frequency of 2280Hz in either direction. An article in the Post Office Electrical Engineers’ Journal explained how it worked. The higher frequency made it less likely to be imitated by speech and a ‘guard tone’ detector prevented operation if other frequencies were also present.

About the late 1960s there was a lot of publicity for the so-called ‘Phone Phreakers’ in the USA. The American telephone system also used a tone signalling system with a single frequency of 2600Hz for line control. Number signalling used dual-tone multi-frequency tones, much as do present-day phones.

One of the phreakers discovered that a popular brand of breakfast cereal was giving away plastic whistles which were tuned exactly to 2600Hz. Hence this gentleman adopted the soubriquet “Cap’n Crunch” after the cereal.

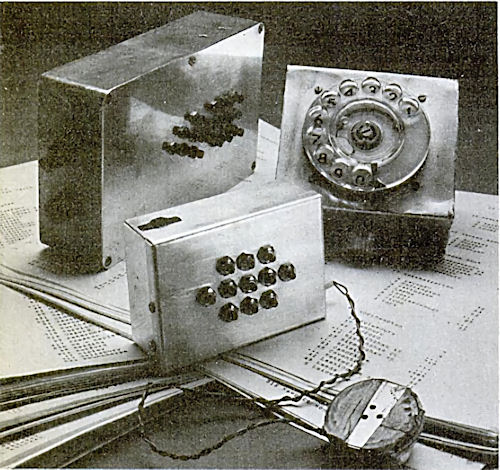

Many companies in the US issued free-of-charge long-distance phone numbers to encourage customers to contact them. Using the 2600Hz tone it was possible to clear such a call to a distant number and then reconnect to any other desired number by sending the 2600Hz tone it was possible to clear such a call to a distant number and then reconnect to any other desired number by sending the multi-frequency digit tones. Production of devices to produce all the required tones, known as a ‘Blue Box’, became prolific. Tones were fed into the telephone handset using a telephone receiver earpiece. Picture, left, Blue box in the Powerhouse Museum [Maksym Kozlenko, creative commons]

Legendary founder of Apple computers, Steve Wozniak, built a number of these which were marketed by fellow founder, Steve Jobs. A rare example was auctioned in 2020 with starting bids in the range $8,000 to $12,000. See the Auction catalogue page.

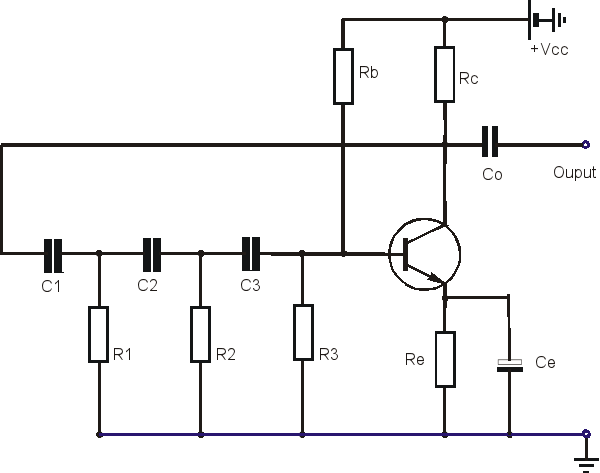

Naturally experimenters in the UK were curious to see if similar wizardry could be employed here to work with British AC9 signalling. The lack of a suitable free plastic whistle led to simple electronic oscillators, such as the phase shift circuit, which used only resistors and capacitors – no awkward inductors needed. A single transistor would suffice – operational amplifiers were a rarity then.

Phase shift oscillator

The whole circuit, including a battery would fit conveniently inside a tobacco tin. Tones could be injected into a telephone using an earpiece held over the microphone as in the US Blue Box..

Needless to say, it worked a treat. A long tone cleared an existing call and subsequent pulses of tone seized the circuit and routed a call. Such devices gained the nickname ‘Bleepers’ for obvious reasons as they went ‘bleep, bleep, bleep’.

Bleepers and code lists [Duncan Campbell?]

Using back doors and bleepers it was now possible to explore the trunk network. At that period virtually all major towns had a manned switchboard accessed by dialling 01 on an incoming circuit. This would appear to the operator as if it had come from another operator, so using the correct terminology was important. The operator would answer by announcing the town’s name, which was all that a researcher needed. Having noted the destination all the researcher need say was something like, “Sorry [Placename]. Misroute. Clear down.” Then they would clear the call and try the next code to see where it went.

In this way a comprehensive dialling code book could be assembled showing the routings from the various trunk exchanges around the country.

International Subscriber Dialling (ISD) was introduced in 1963, initially between London and Paris, later extended to other areas of Europe. Continental circuits could be accessed via the London gateway from the inland trunk network.

Signalling to Europe used a different system called CCITT 4 (Comité consultatif international téléphonique et télégraphique – part of the International Telecommunication Union). It used two frequencies, 2040Hz and 2400Hz in a binary combination for digits and also for line control. Details of this and the country codes needed were helpfully published by the CCITT in a series of handbooks known by their colour (Blue Book in particular).

As you might expect, a number of UK enthusiasts built devices to simulate the tones. By this means it was possible to extend calls to countries not available for public dialling.

Signalling to North America used a different code called CCITT 5, which bore a striking resemblance to the tones from the previously mentioned Blue Box.

1972 saw the beginning of the end for a group of independent telephone fiddlers who played around with the telephone system out of curiosity and for pleasure.

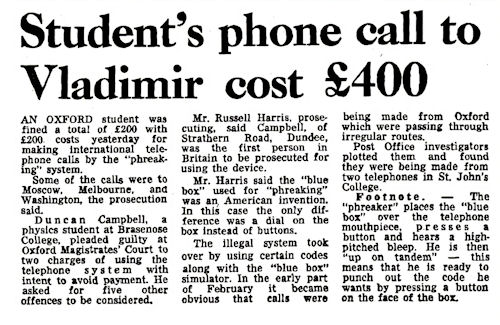

The Post Office investigators began to catch up with experimenters. First to hit the headlines in March was Oxford student Duncan Campbell.

The Daily Telegraph wrote:

“Post Office investigators are trying to break a big ring of “phone phreaks,” it was disclosed yesterday after a 19-year-old undergraduate was fined a maximum £200 with £200 costs at Oxford magistrates' court for making telephone calls illegally and free of charge. Duncan Wilson Archibald Campbell, of Strathern Road, Dundee, a second-year student at Brazenose College, was said to have made calls to America - including a Los Angeles brothel - and to Russia.”

By now the Post Office Investigation Branch was hot on the trail of others of the fraternity.

Over a period of a few years a disparate group of mostly young men – many were recent graduates from some of our most prestigious institutions – had started meeting and corresponding (no email in those days) to discuss and conduct research into the structure and fabric of the British telephone network. They had already discovered the delights to be found in the Post Office Electrical Engineers’ Journal, but wanted to know more about how the phone system was put together. To that end they employed a variety of technical devices and methods – some of dubious legality, it has to be admitted.

A meeting of these men had been arranged at the flat of two of them in West London on 7th October, 1972. To their surprise the premises were raided by the Metropolitan Police and all 19 were arrested and charged with conspiracy to defraud.

This event was not reported in the press at the time, though it must have been the largest ‘phone phreaking’ bust of the Investigation Branch to date. However, when the case came to court 12 months later it made headlines in the national press and forms the subject of the next article.

Next: 3. - The Telephone Trial of the Century

Previous: 1. - Fraud or fun?