Sam Hallas' Website

This is the concluding article from a series I prepared for the Telecomms Heritage Journal about how certain folk cheated the phone system, some times it was fraud but at other times it was just for fun and how it all ended.

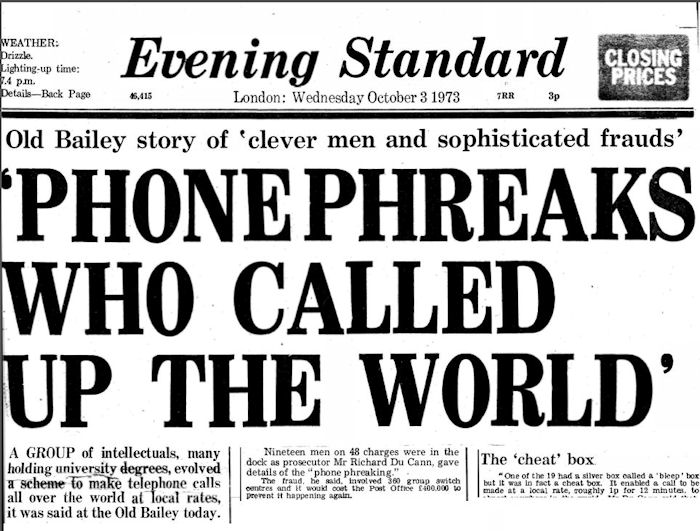

This article was prepared to commemorate the fiftieth anniversary of the events described. On the 3rd of October 1973 a group of mostly young men faced charges of conspiracy to defraud the Post Office. This was not taking place in some back-street Crown Court in a suburb, but at the most important Central Criminal Court, Old Bailey, in London.

It would seem that the aim of the Post Office Investigation Branch announced in March the previous year to “break a big ring of phone phreaks,” had come to fruition. It was obviously intended to be the “Telephone Trial of the Century” to send a message to everybody engaged in cheating the Post Office that they would be found out and brought to justice.

The men had all been arrested whilst attending a meeting at the home of two of them in a flat in West London the previous October.

The prosecuting counsel stated, “They have used and abused the telephone system both in the United Kingdom and abroad on an increasing and important scale, advancing at the same time not only their own but each other's knowledge of the system. For that purpose they exchanged information by letter about highly technical matters. Their thoroughness was as painstaking as it was sophisticated.”

Counsel went on to say that all the men had considerable training or experience of telephones and telecommunications. "Many hold degrees from various universities; two were students at universities; some were very practised on the practical side in this particular field; and two had been employed by the Post Office. Intellectually, in this field, all these defendants are of some stature." – Most flattering!

He added that it would cost the Post Office £400,000 to prevent such a fraud again, conveniently glossing over the fact that better design might have prevented it in the first place. The defendants also possessed a list of ‘interesting numbers’, he said, with national and international connections, such as the Kremlin and Buckingham Palace. The defence later reminded the jury that those details were in the public telephone directories. One defendant, Robert Hill, remarked, "Almost all the paperwork could be dismissed like this (given time) and even the remainder was not illegal, though some of it was not actually published."

<

<Several exhibits were produced of equipment seized at the meeting. A number of tone generators, or bleeps, were shown which simulated the signals on telephone trunk calls. At least one also produced tones for overseas systems and one wag christened it a 'Mighty Wurlitzer'. For the benefit of younger readers, Wurlitzer is a maker of cinema organs, containing many switches and keyboards, which can imitate a host of other instruments.

Robert Hill continued, "With these came paperwork galore: Japanese dialling code books, maps of the North of Scotland, computer printouts, Xeroxed copies of the Warsaw telephone directory and even a sketch of a London underground ticket. Then there are the sundries like bent wire and an ordinary microswitch. Altogether, half-a-dozen trunks full of detailed evidence. The jurymen are scarcely visible behind heaps of goodies provided by the prosecution. It is a memorable sight, the look of joy in their eyes, as the court usher delivers another heap - six copies of a photograph album of the defendants, perhaps, or six copies of the A-D section of the London telephone directory even." One juror admitted afterwards that though most of the paperwork was mind-numbingly dull some of the defendants’ correspondence was frankly hilarious.

"The prosecution, too, was well provided: a large demonstration had been built showing how the telephone system worked, glistening with flashing lights and illuminated boxes and standing some seven feet high. There was a beautiful red telephone coin box there, in case someone couldn’t resist a quick play. The Post Office representatives failed miserably in trying to obtain free calls from this. As the Judge remarked, ‘You would probably be better off if you asked for volunteers'."

Note that the main charges were of conspiracy. It was never made clear during the trial what constituted ‘conspiracy’, but it is sobering to know that, for instance, a person convicted of conspiracy to deposit litter could be fined £10,000 and in addition could be sentenced to 15 years in prison considerably more than the maximum penalty if they had actually committed the crime of littering.

In retrospect it seems that the defendants were not denying conspiring, but that they only conspired to research the public telephone network and not to commit fraud.

After ten days of evidence, the judge, Mr Justice McKinnon QC, consulted defence barristers and let it be known that if anyone changed his plea to ‘guilty’ he would be fined about £100, and a similar amount of costs. He also suggested that costs would be far higher if anyone were found guilty at a later stage.

Almost immediately ten of the defendants changed their plea, pretty certainly out of expediency. Their reasoning must have run that there was a 60% probability of acquittal after two months, but a consequent loss of pay of maybe £400. The 30% remaining probability of conviction could lead to high costs, say £500, and maybe be even loss of their job. Six people were fined £100 with £100 costs, three fined £50 with £50 costs and one only £25 on each count.

As reported the following day in the the Daily Telegraph, in summing up their convictions the judge described the defendants as being like small boys who would like to drive a steam engine. "They wanted to drive the Post Office machinery themselves."

He continued, "It seems to me these defendants must all be basically excellent and loyal citizens, By dint of their own researches they have come by information which enables them to get inside exchanges belonging to Ministries and Departments of State. No one has for a moment suggested they have made any use of that which is detrimental to the State."

The prosecution said the alleged conspiracy went on from 1968 to October 1972. The men, many holding university degrees, evolved a scheme to cheat the Post Office. The Judge told the 10 being sentenced that men of their qualifications could be of great service to the State. “I hope you continue to give that service,”

Of the remaining defendants, Robert Hill later wrote, "The nine left were characterised by being either very innocent, very pigheaded, or both", in which last category he included himself. In fact, all charges against him were dropped shortly after that.

The trial dragged on for another month until 13th November when the jury found all the remaining eight defendants not guilty. In summing up their acquittal Mr Justice McKinnon QC, said, "Your trial is over and now I can congratulate you. I never did think that you were dishonest and I never said so.” Urging future caution he went on, “But you must have learned something from this trial. Do exercise some care and judgment in future because men of your distinction ought never to find themselves in the dock at the Central Criminal Court."

If the Post Office Investigation Branch thought that the case would produce a mass of convictions and prison sentences they must have been sadly disappointed. Maybe they chose the wrong people to prosecute. Instead of a bunch of telephone nerds who only wanted to dig into the phone system, they should have pursued other cases where back doors into the trunk network had been exploited by crooks for gain. These would have been much more salutary if given the Old Bailey treatment.

Robert Hill wrote afterwards, "Half of those who pleaded guilty were certainly less involved than some who got off." The estimated cost would have been about £70,000 meaning that the main beneficiaries were the lawyers.

So the "Telephone Trial of the Century" turned out to be rather a damp squib of the century instead. The defendants went on to lead otherwise blameless careers, a good number in the telecommunications industry.

Previous: 2. - New naughtiness

Start: 1. - Fraud or fun?