Sam Hallas' Website

A Short History of Telegraphy - 1 Beginnings

By Alan G. Hobbs (G8GOJ) and Sam Hallas (G8EXV)

It is well nigh impossible to describe the entire history of the electric telegraph in a few pages, but I hope we can still give you an insight into

the ingenuity and technology of the early inventors - the pioneers who laid the foundations for today’s complex, computer based systems.

Click the images for a larger version. Click 'Close' or press ESC to return. Main text is the original 1987 article

New text is shown in italics I have added a supplement, Part 4, to summarize the changes I have seen in telegraphy since the article was written up to 2014.

The Dawn of Time

Since earliest times human beings have wanted to communicate at a distance.

Primitive Man could keep hunting parties in touch about the movement of

game by means of smoke signals. Military man was able to co-ordinate his

armies. The ancient Greeks used mirrors to reflect the sun’s rays at the

battle of Thermopylae.

All sorts of ways have been found of passing messages and they all rely

on extending the human senses of sight or hearing in some way.

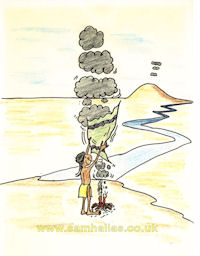

The explorer and journalist, Stanley, - famous for having found Dr Livingstone

- when he was travelling the Congo river (now the River Zaire), was mystified

to find that the villagers knew he was coming in advance. Of course the

answer to the mystery was the talking drum. The drum is made from a tree

trunk, hollowed out and shaped. Depending on how you hit it, different

notes are produced which can sound like the local language. A means of

communicating ideally suited to a country with dense forest, where one

cannot see from one village to the next. Another very apt name for the

drums is the ‘Jungle Telegraph’. [Picture & video: Pathé 'Look at Life']

The explorer and journalist, Stanley, - famous for having found Dr Livingstone

- when he was travelling the Congo river (now the River Zaire), was mystified

to find that the villagers knew he was coming in advance. Of course the

answer to the mystery was the talking drum. The drum is made from a tree

trunk, hollowed out and shaped. Depending on how you hit it, different

notes are produced which can sound like the local language. A means of

communicating ideally suited to a country with dense forest, where one

cannot see from one village to the next. Another very apt name for the

drums is the ‘Jungle Telegraph’. [Picture & video: Pathé 'Look at Life']

Video of talking drum at half speed

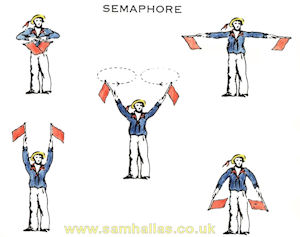

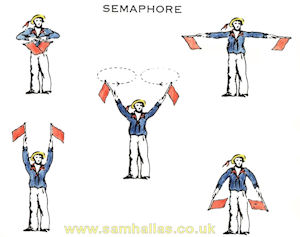

Conversely, one place where one can see for miles is at sea. And navies

have used flags and semaphore for centuries. Using it on land is more difficult.

To signal as far as possible some high vantage points are needed - even

better if you can put it on a tower.

Mechanical Telegraphs

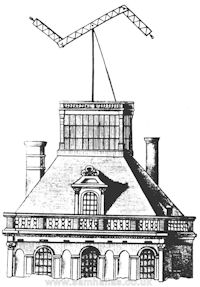

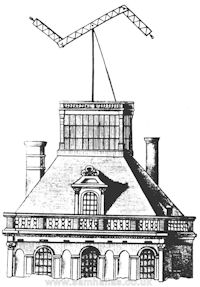

Just such a system was invented in the 1790s by Frenchman Claude Chappe

- a system of wooden shutters on a tower, which could show 63 different

signals. [Correction: The Chappe system used a pair of semaphore arms as illustrated left.] Naturally, military leaders quickly grasped the importance of systems like this and Napoleon made good use of the Chappe telegraph in

his invasion of Italy. A system was made linking London to the naval dockyards

at Portsmouth. Needless to say, fog or bad weather frequently interrupted

communication. [Picture: Public domain via Wikimedia commons]

[Watch this YouTube video of Prof Nigel Linge demonstrating a Chappe telegraph replica]

Addendum: The British military telegraph described above would have looked like this model on the right in the National Museum of Scotland.

Definition

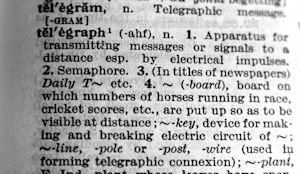

These semaphore type systems were the first to be described as a telegraph.

Telegraph was a word coined in 1792 from the Greek, tele, afar, and graphos,

a writer. Concise Oxford Dictionary

First Steps with Electricity

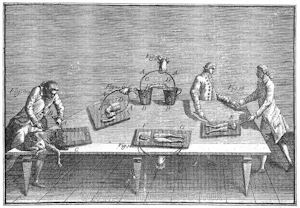

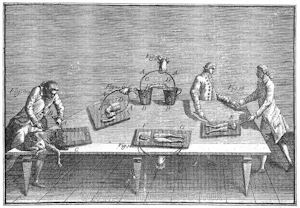

But electricity was on its way to assist the art of telegraphy. In the

second half of the 18th Century there were important discoveries about

the nature of electricity though it remained a mysterious fluid. Galvani

conducted experiments with frogs’ legs to show the effects of electricity.

Volta developed a battery, giving a steady source. Other experiments showed

that transmission along wires was virtually instantaneous. This held out

tantalising prospects for telegraphy. The first problem was to detect the

presence of an electric current. [Picture: Frog, BT; Galvani, Public Domain]

But electricity was on its way to assist the art of telegraphy. In the

second half of the 18th Century there were important discoveries about

the nature of electricity though it remained a mysterious fluid. Galvani

conducted experiments with frogs’ legs to show the effects of electricity.

Volta developed a battery, giving a steady source. Other experiments showed

that transmission along wires was virtually instantaneous. This held out

tantalising prospects for telegraphy. The first problem was to detect the

presence of an electric current. [Picture: Frog, BT; Galvani, Public Domain]

Lesage’s telegraph used pith ball electrometers and another early idea

from S.T. van Soemmering was to use the electrolysis of water to detect

the current. But an important breakthrough came in 1810 when Ampere and

Oersted showed that the current in a wire could deflect a magnetised needle.

By 1836 a needle telegraph had been developed by Baron Pawel Schilling.

This was seen by the young William Cooke. [Picture: Science Museum collection]

The Cooke & Wheatstone Era

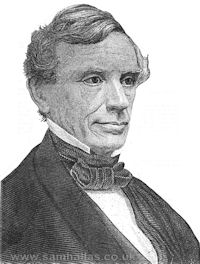

William Fothergill Cooke

Cooke immediately saw the possibilities of a telegraphic system linking

the major towns in the country. But he was unknown to investors. So to

get commercial support for his scheme he turned to Professor Charles Wheatstone

as partner. It was in 1837 that Cooke & Wheatstone devised the first

practical telegraph, which was known as the five needle system. This was

an alphabetical system with five needles, controlled by five separate wires. More detailed information at the

Science Museum, London

[Picture of Cooke: Public Domain] (The 5-needle instrument in the Science Museum, London, on the right is a replica made for museum display, probably, in the 1930s. Collector Fons Vanden Berghen has an identical one shown here. And here he is demonstrating it.)

The needles pointed to to the desired letter. It only remained for the

receiving operator to note down the letters in order as received.

[Watch this YouTube video of Prof Nigel Linge talking about and demonstrating a 5-needle replica, or a more recent, excellent demonstration and explanation by Wim der Kinderen here]

Section of 5-needle cable

2-needle telegraph

The five needle system was clumsy to operate and, because it needed five wires,

was expensive to cable. It was not long before it was replaced by the double

needle system, with only two wires, using a code to indicate the letters.

The first telegraphs were the Railway Companies’ private systems, but the

double needle telegraph was the first to be used for a public telegraph

from Paddington to Slough in 1841.

Morse Code Begins

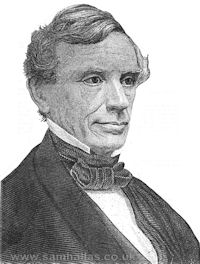

Samuel Finley Breese Morse

In turn the double needle gave way to the single needle system, using

only one wire and the famous code developed by the Americans, Samuel Finley

Breese Morse and Alfred Vail. A further development, the Highton single needle system,

introduced in 1837 employed the Morse code, transmitted from a device known

as a commutator. The commutator had two keys, which made current flow in

opposite directions in the line, corresponding to a dot and a dash. The single-needle telegraph was widely used on British railways for communications between signalboxes. See my single-needle article

Morse operators at the Central Telegraph Office

Originally, the receiving operator had to watch the needle and write down

the letters. This made it very slow, and pretty soon means were found to

make the signal audible to the operator. By putting two different type

of stop pins, two distinctive sounds were made - a sort of ‘ting’ and ‘tong’.

The operator now had only to concentrate on listening to the sounds, and

write down the letters. (Once again Fons Vanden Berghen is able to demonstrate one from his collection

Single needle & double-plate sounder

Experience soon showed that a skilled operator could interpret Morse

code from the long and short periods of the dots and dashes. As a result

the familiar single current Morse key and sounder came into use. This is

the first data transmission system which is still in extensive use today

on the amateur bands. [Morse operators picture: Science Museum/ HPL] (Notice that the Morse sounder on the operator's left is mounted in a wooden box to amplify the sound.

Easy as ABC with Wheatstone

Charles Wheatstone

To get away from the need for highly trained operators, Sir Charles

Wheatstone invented the ABC system in 1840. It indicates the letter directly

by a pointer, like a clock hand. There is a hand generator on the front,

a dial with 30 keys round the edge and a pointer. The whole thing was known

as a communicator. A separate receiver also had a single pointer.

To work it one pressed the key for the letter wanted and wound the generator.

The pointer would go round until it reached the key pressed and then it

disconnected the generator. Pressing another key then allowed the pointer

to rotate to the next letter and so on.

The generator sent alternating half cycles of current to the line and

the receiving pointer moved round a letter at a time, like a stepper motor,

till it reached the letter being sent.

It was pretty simple, robust, and needed little skill to operate. Speeds

were up to about 15 words per minute.

See one in action in the Scottish Islands in the 1930s from The Islanders (PO Film Unit) in the clip below, left. On the right Richard Youl (YouTube ID tressteleg1) demonstrates a Wheatstone ABC machine in the Telstra Museum in Sydney, Australia. Can you see what message he sends?

ABC telegraph in use on a Scottish Island in the 1930s

ABC telegraph at Telstra Museum, Sydney

These articles copyright 1987-2014, AG Hobbs & SM Hallas.

Back to Top

Part 2

Part 3

Part 4 - Supplement

Telecomms Index

The explorer and journalist, Stanley, - famous for having found Dr Livingstone

- when he was travelling the Congo river (now the River Zaire), was mystified

to find that the villagers knew he was coming in advance. Of course the

answer to the mystery was the talking drum. The drum is made from a tree

trunk, hollowed out and shaped. Depending on how you hit it, different

notes are produced which can sound like the local language. A means of

communicating ideally suited to a country with dense forest, where one

cannot see from one village to the next. Another very apt name for the

drums is the ‘Jungle Telegraph’. [Picture & video: Pathé 'Look at Life']

The explorer and journalist, Stanley, - famous for having found Dr Livingstone

- when he was travelling the Congo river (now the River Zaire), was mystified

to find that the villagers knew he was coming in advance. Of course the

answer to the mystery was the talking drum. The drum is made from a tree

trunk, hollowed out and shaped. Depending on how you hit it, different

notes are produced which can sound like the local language. A means of

communicating ideally suited to a country with dense forest, where one

cannot see from one village to the next. Another very apt name for the

drums is the ‘Jungle Telegraph’. [Picture & video: Pathé 'Look at Life']